How The Most Dangerous Ideas Wind Up as Policy

Political science explains why you shouldn't dismiss radical, extremist views.

I often write about topics that make my blood boil.

That includes issues like the rise of extremist ideologies and movements, particularly of the online and red-pilled kind.

In other words, the sort of things that probably reassure some people in the belief that if aliens were ever to launch a full-scale invasion of our planet, it’s best just to surrender and hope that whatever they’ll come up with is better than this.

But every now and then, I get asked: what’s the point in talking about the most vile beliefs out there?

After all, so much of what we see lately — including on mainstream social media platforms — is essentially clickbait-style extremism.

From anti-feminists like Pearl Davis, who claims ‘women shouldn’t have the right to vote’ to ‘incel influencers’ like Sneako, who recently publicly called for ‘death to gays,’ there’s no shortage of money and fame-hungry people armed with microphones and an array of misogynistic, homophobic, racist and otherwise hateful ideas.

So why even acknowledge their existence when they clearly profit off riling others up and saying the most inflammatory and outrageous things you could imagine?

Wouldn’t it be better to ignore them altogether, especially when their ideas seem self-evidently false or far too outrageous to be considered seriously by anyone with half a brain?

Well. However horrifying or laughable those might be, and whether or not we choose to ignore them, they’re still seeping into the public consciousness.

And that alone can have more impact than you think.

Today’s radical idea could be tomorrow’s mainstream policy

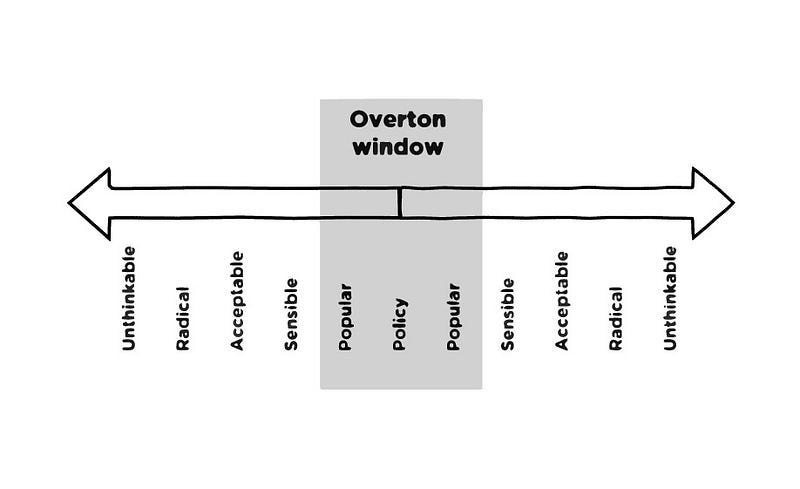

You might’ve already heard about the Overton window.

It’s a concept named after Joseph Overton, a political theorist, that designates the range of policies or, more broadly speaking, ideas that are largely acceptable within public opinion and mass media.

As Overton argued, various policy options on a given issue exist on a spectrum of public acceptability, ranging from unthinkable, radical, acceptable, sensible to popular and policy. Everything outside the Overton window is considered fringe, and everything inside is part of the mainstream conversation.

Of course, the window isn’t static. It can significantly shift or expand over time. Not that long time ago, we used to employ children in factories. Own other human beings. Enforce segregation. Deny women the right to vote. Oppose same-sex marriage.

But as the Overton window has gradually shifted due to the slow evolution of societal values and norms towards more progressive ones, what was once wildly popular is mostly unthinkable nowadays. And what was once merely acceptable became popular or even imminent policy.

This doesn’t always happen through a gradual shift, though.

Overton also argued that the easiest — and quickest — way for politicians and people in power to move the window was to force people to consider ideas at the extremes, as far away from it as possible. Because even when they reject it, it makes all the less extreme ones seem acceptable by comparison and, ultimately, helps move the window in that direction anyway.

Donald Trump’s campaign and administration is probably one of the most notable — and recent — examples of that approach.

But it’s not just those in power, on either side of the political equation, who influence what becomes the mainstream public-political discourse. It’s also think tanks, activists, advocates, academics and… anyone with a large enough following. In particular, on social media.

The rise of globalisation and the Internet have empowered people to express themselves, find others who share their views, band together to break into the mainstream, and, to some extent, shake up the status quo that we have come to know, working around the barriers of traditional media and academic journals.

Some scholars have even suggested that something as seemingly innocent as… memes, often used as propagandising and recruitment tools for the alt-right, could be a successful tactic to shift the Overton window.

All of this forces us into an equal parts unusual and dangerous situation.

In particular, consider another important trigger for abrupt and large shifts in the Overton window — society-wide crises.

Extreme circumstances often lead to extreme sentiments

It’s a pretty well-documented phenomenon in economics and political sciences that whenever times get tough, many things change. And not exactly for the better.

Economic shocks — unexpected events with large-scale consequences — tend to exacerbate poverty, inequality and economic uncertainty, all of which can then lead to public distrust in the current government, polarisation and the rise of extremist movements.

After the Great Depression hit, well, we all know how that story ended.

The most extreme movements in our history likely would never be able to grow to the proportions they grew to if it weren’t for the crises that took place shortly before they became popular. Because it’s precisely when society is put out of the equilibrium that it becomes easy for the Overton window to be shifted or expanded.

According to a recent study conducted among nearly 20,000 respondents within 22 countries, in the aftermath of a simulated economic shock, there’s indeed an uptick in negative stereotyping of people who don’t belong to our ‘in-group’ — a social group to which a person psychologically identifies as being a member. And that’s true even if positive stereotyping of ‘out-groups’ had been widespread before.

Unsurprisingly, study after study shows that such events correlate with more negative attitudes towards immigration as well.

You could also make a strong case that as economic shocks hit and more and more people struggle to make ends meet, our ability to share in and care about the feelings of others may be diminished. After all, research shows that when our cognitive resources are depleted, empathy lessens.

All of that means that in times of crisis, those interested in sowing the seeds of societal instability and conflict between various groups, either by using pre-existing prejudices or creating entirely new ones, might have a much easier time doing so.

People are already miserable, angry and looking for someone to blame, and so as long as you’re able to convince them that whatever you plan on doing will lift them from their misery and punish those responsible for it, you can manipulate public discourse in whichever direction you want.

How is that relevant right now, though?

Well, unfortunately, the last couple of decades can be probably best described as the era of the ‘polycrisis’ — several once-in-a-lifetime events happening all at once, or one right after another, contributing to an exaggerated sense of conflict.

If we’re not dealing with the aftermath of the financial crisis, we’re dealing with the aftermath of a pandemic. Or the war in Ukraine. Or extreme weather events. Or the cost of living crisis.

It’s a no-brainer that during the same time, and particularly the last half a decade or so, there’s been a rise of populist extremism and polarisation across the globe and that some of the things that were once ‘unthinkable’ now moved to ‘acceptable’ part of the Overton window’s spectrum.

Extreme circumstances often lead to extreme sentiments, which then lead to extreme ideas.

Only one day, we might not even consider them as ‘extreme’ anymore.

We shouldn’t wait until it’s too late to acknowledge what’s happening

Urban legend has it that if you put a frog in a pot of boiling water, it will instantly leap out.

But if you put it in a pot filled with pleasantly tepid water and gradually heat it, the frog will remain in the water until it boils to death, as it cannot detect the gradual increase in temperature until it’s too late.

And although this story has proven to be a mere myth — if you throw a frog into a pot of boiling water, it will be hurt pretty badly but likely manage to get out — it’s a useful metaphor for human behaviour.

We tend to accept things that creep up on us slowly but steadily, even when they take control of our lives, and only realise the severity of the situation when it reaches catastrophic proportions.

Of course, it’s easy to close your eyes and pretend that nothing bad is happening, particularly if it’s not happening to you or anyone in your in-group. Or assume no one will take people loudly and proudly cashing in on the most unhinged and dangerous of ideas seriously.

Only not acknowledging them doesn’t automatically push them to oblivion.

And several extremist-related attacks in the years, like the incel shootings, as well as bullying and harassment towards marginalised groups like the LGBTQ+ community, show that some people, unfortunately, do take those ideas seriously.

Besides, whether we like it or not, those radical ideas can shift the Overton window by making less radical ones look ‘acceptable’ in comparison and move it in the desired direction. Or perhaps the goal of all those alt-right extremist communities and individuals isn’t to shift it but smash it all together and then gradually rebuild it in their image.

Either way, that’s not to say we should give them even more opportunities to voice their beliefs or engage in petty debates that often lead nowhere.

But we can — and should — talk about the things they’re disseminating and pushing for and why.

In particular, since we’re likely not getting out of this ‘polycrisis’ anytime soon, and we’ll likely witness more and more people and groups try to take advantage of that to sow division and hatred in years to come.

The rear-view mirror of history gives us a very clear warning: extremist movements might seem too ridiculous or too small to bother with until they aren’t anymore.

That’s the moment when they successfully filled the void created by fear and resentment and ignorance with hatred.

And if we’re not too careful, we might wake up in boiling water one day and wonder how on earth we let that happen.

Read more by Katie Jgln here and on The Noösphere. To support Katie's work directly, you can buy her a coffee.